Historical Roots and Evolution of Chinese Poetry

Chinese poetry boasts an unbroken tradition dating back over 3,000 years. From the ancient “Book of Songs” (Shijing) to the Tang and Song dynasties, poetry has played a central role in Chinese society. Each era introduced new forms and themes, but certain fundamental characteristics have endured.

Conciseness and Imagery

One hallmark of Chinese poetry is its brevity. Poems often express profound emotions and complex ideas using very few words. This is partly due to the monosyllabic nature of Chinese characters, which pack layers of meaning and allow poets to paint vivid imagery with minimal language. The result is a style that values suggestion over explanation, encouraging readers to infer deeper meanings.

Parallelism and Structure

Chinese poetry often employs parallelism, where lines mirror each other in structure and meaning. This can be seen in forms like “regulated verse” (律诗 lǜshī), which requires strict patterns of tone and parallel structure. Such organization not only enhances the poem’s musicality but also challenges the poet’s linguistic creativity.

Rhyme and Tones in Chinese Poetry

Rhyme is another defining characteristic of Chinese poetry, but it differs significantly from rhyming in English or other Western languages.

End Rhymes and Rhyme Schemes

Traditional Chinese poems, especially those from the Tang and Song periods, often employ end rhymes. However, the rhyming is usually based on the final syllable of each line, with a particular focus on matching vowel sounds rather than consonants. Rhyme dictionaries, such as the “Pingshui Yun,” were developed to standardize which characters could rhyme, reflecting the importance of this feature.

The Role of Tones

Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language, and tones add another layer to poetic composition. Poets must consider not just rhyme, but also the tonal pattern of each line. Classical forms like the regulated verse require alternating level (平 píng) and oblique (仄 zè) tones, creating a rhythm that is both musical and harmonious.

Flexible Rhyming in Modern Poetry

While ancient poetry adhered strictly to rhyme and tonal rules, modern Chinese poetry is more flexible. Free verse is common, and poets experiment with new forms and expressions, though the tradition of rhyming and structured meter still influences contemporary works.

Symbolism and Cultural Significance

Chinese poetry is renowned for its use of symbolism and allusion. Nature imagery—such as the moon, mountains, rivers, and flowers—serves as a metaphor for human emotions and philosophical concepts. Allusions to classic texts and historical events enrich the layers of meaning, making knowledge of Chinese culture essential for full appreciation.

Challenges and Rewards for Language Learners

Learning to read and appreciate Chinese poetry offers unique challenges, particularly for non-native speakers. The compactness of language, the importance of tones, and the cultural references can be daunting. However, engaging with poetry can dramatically improve language skills.

- Vocabulary Expansion: Poems introduce learners to high-frequency words, classical expressions, and idioms.

- Tonal Awareness: Practicing rhyming poetry sharpens understanding of Mandarin’s tonal system.

- Cultural Literacy: Poetry offers deep insights into Chinese history, philosophy, and values.

Tips for Learning Chinese Poetry

- Start with short, famous poems like those by Li Bai or Du Fu.

- Listen to recitations to develop an ear for rhythm and tones.

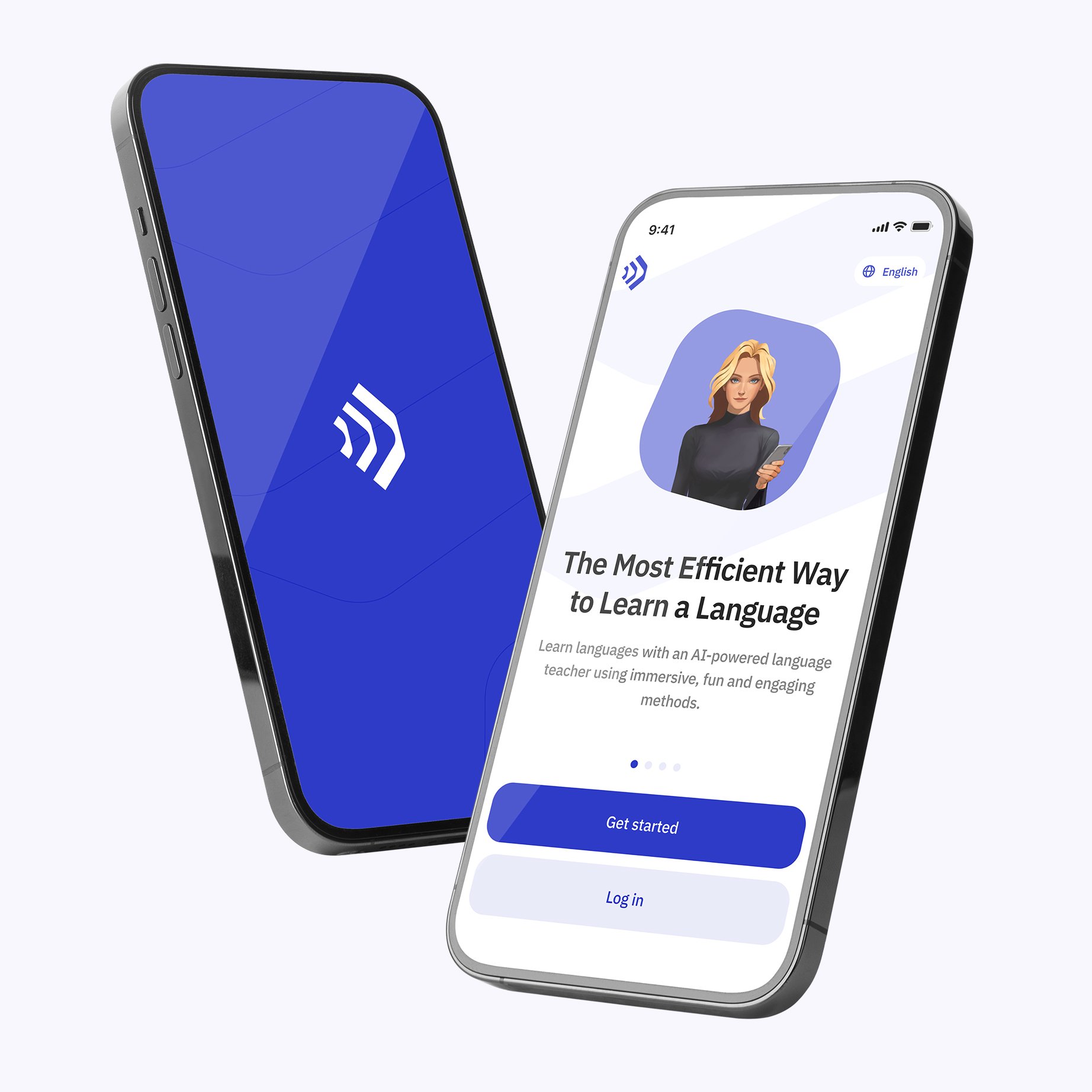

- Use resources such as Talkpal’s AI tools to practice pronunciation and comprehension.

- Study the meanings behind common symbols and allusions.

- Try composing simple poems to internalize patterns of rhyme and tone.

Conclusion

The unique characteristics of Chinese poetry and rhyming set it apart as a literary form and as a language-learning tool. Its conciseness, parallel structure, intricate rhyming, and cultural richness provide a window into the soul of Chinese civilization. For learners using platforms like Talkpal, exploring Chinese poetry is not just an academic exercise—it’s a journey into the heart of the language itself.