The Four Cases: Nominative, Accusative, Dative, Genitive

Perhaps the most daunting aspect of German grammar is the case system. Unlike English, German uses four cases to indicate the function of nouns and pronouns in a sentence. These are:

- Nominative – for the subject of the sentence

- Accusative – for the direct object

- Dative – for the indirect object

- Genitive – for possession

Each case changes the article and sometimes the noun ending. For example, “the man” can be der Mann (nominative), den Mann (accusative), dem Mann (dative), or des Mannes (genitive). This complexity often leaves learners confused about which form to use and when.

Gendered Nouns: Der, Die, Das

German nouns are either masculine, feminine, or neuter, each with its corresponding article: der (masculine), die (feminine), and das (neuter). Unfortunately, there are few reliable rules for determining the gender of a noun, so learners must often memorize each one. For example, das Mädchen (the girl) is neuter, not feminine, which can be perplexing.

Word Order: Main Clauses vs. Subordinate Clauses

German word order can be tricky, especially when it comes to verbs. In a main clause, the verb typically comes second. However, in subordinate clauses (introduced by words like weil or dass), the verb is pushed to the end of the sentence. For example:

- Main clause: Ich gehe ins Kino. (I am going to the cinema.)

- Subordinate clause: Ich gehe ins Kino, weil ich den Film sehen will. (I am going to the cinema because I want to see the movie.)

This rule often trips up learners, especially in longer sentences.

Separable and Inseparable Prefix Verbs

German loves its compound verbs, many of which come with prefixes that can be either separable or inseparable. Separable verbs (like aufstehen – to get up) split in the present tense: Ich stehe um sieben Uhr auf. (I get up at seven o’clock.) In contrast, inseparable verbs (like verstehen – to understand) never split: Ich verstehe dich. (I understand you.) Knowing when to separate the prefix is a common source of confusion.

Adjective Endings: Declension After Articles

Adjectives in German take different endings depending on the case, gender, and whether they follow a definite article, indefinite article, or no article at all. For instance:

- Der schöne Tag (The beautiful day – nominative, masculine, definite article)

- Ein schöner Tag (A beautiful day – nominative, masculine, indefinite article)

- Schöner Tag (Beautiful day – nominative, masculine, no article)

The variety of adjective endings can be overwhelming even for intermediate learners, making practice and exposure essential.

Modal Verbs and Infinitive Placement

Modal verbs (like können, müssen, wollen) also affect word order, requiring the main verb to be placed at the end of the sentence in its infinitive form. For example: Ich kann Deutsch sprechen. (I can speak German.) This rule, combined with subordinate clause word order, can result in very long sentences with the main verb buried at the end.

Reflexive Verbs and Pronouns

Some German verbs require reflexive pronouns, and the form of the pronoun changes depending on the case. For instance, sich freuen (to be happy) uses a reflexive pronoun: Ich freue mich (I am happy), du freust dich (you are happy). The difference between sich and ihn or ihm can be subtle and confusing for learners.

Conclusion: Practice Makes Perfect

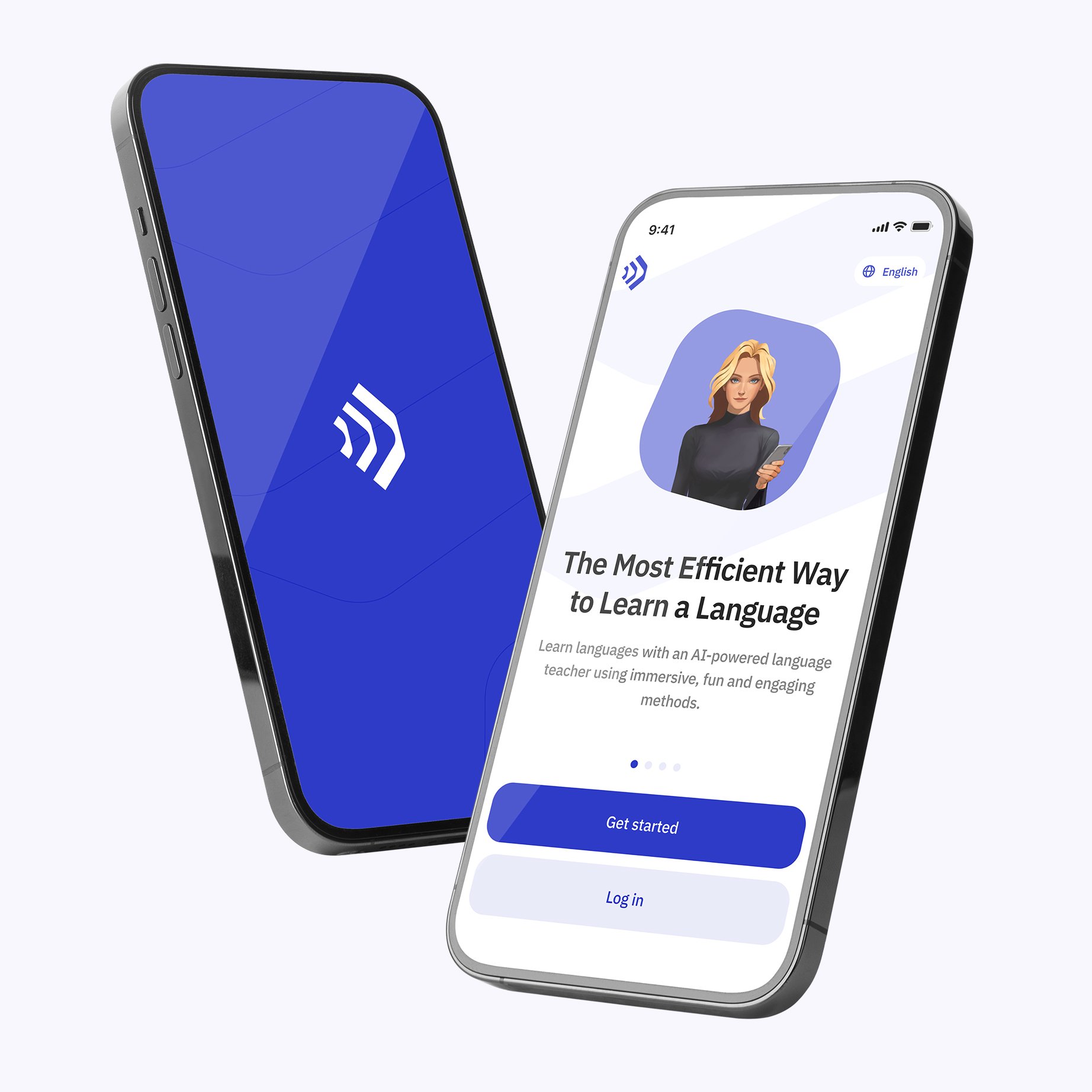

While German grammar may seem intimidating at first, understanding these confusing rules is entirely possible with patience and regular practice. Utilizing language learning tools like Talkpal can help you internalize these patterns through interactive exercises and real-life examples. Remember, every language has its quirks; with time, German grammar will become second nature and open up a whole new world of communication and culture.